Towards A Prayer Book Catholic Sensibility

Reflections on balancing between Conformity and Chaos: being neither fundamentalism nor libertinism.

{part of a series}

Archbishop Rowan Williams, writing Thomas Cranmer: A Prayer Book Catholic? for the Prayer Book Society UK journal Faith and Worship #93, has written a gem of an essay.

In it he admirably gives the sensibility (vibe?) of a Prayer Book Catholic.

A Prayer Book Catholic?

Prayer Book Catholic, for those who haven’t heard the term are, as Williams humorously recounts, those whose use of the “Book of Common Prayer [is] ‘mangled in a funny, High Church sort of way’.” More practically speaking, a Prayer Book Catholic is one who identifies primarily as a Catholic, but views the Book of Common Prayer as a sufficient spiritual framework for English (Anglo-) Catholicism. To be a Prayer Book Catholic means that the BCP is not a insufficient form of worship, and “mangling” it in a funny High Church sort of way is a helpful addition according to that spiritual framework, but not a corrective to insufficient liturgics. Luminaries such as Percy Dearmer & the Alcuin Club (a band name if there ever was one), C.B. Moss, Staley, B.J. Kidd, all connect to this English Catholic form of worship. The term is partially due to the advent of the Ritualists forming a primary spirituality around the practices of Rome, as though the English Church, most especially the Caroline Divines and others in the Anglican Counter-Reformation of the 17th century.

So while Ritualists, seeking to regain continuity with the Medieval as much as Patristic and Reformed spirituality, brought then-contemporary Latin prayers into their practice, Prayer Book Catholics typically use either the Prayer Book alone, or the Prayer Book ‘mangled with High Church’ ceremonial and prayers.

The Tractarians of the early-mid 19th century —primarily a theological ressourcement of English Catholicism, including reading some post-Reformation divines as ‘Reformed’ Catholics— were the theoretical basis. But at the time there was little in the way of recovery of the ceremonial or liturgical continuity the Tractarians sought. Since then, much of Anglo-Catholicism has looked first to Roman (which is to say Tridentine) ceremonial, for in the 19th century the most readily available “extras” were those of Rome or the East.

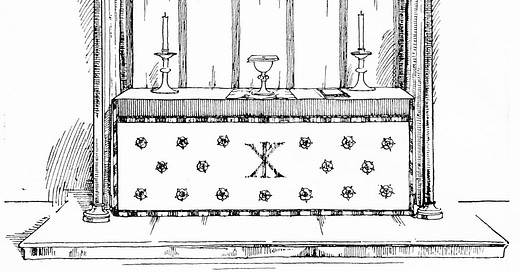

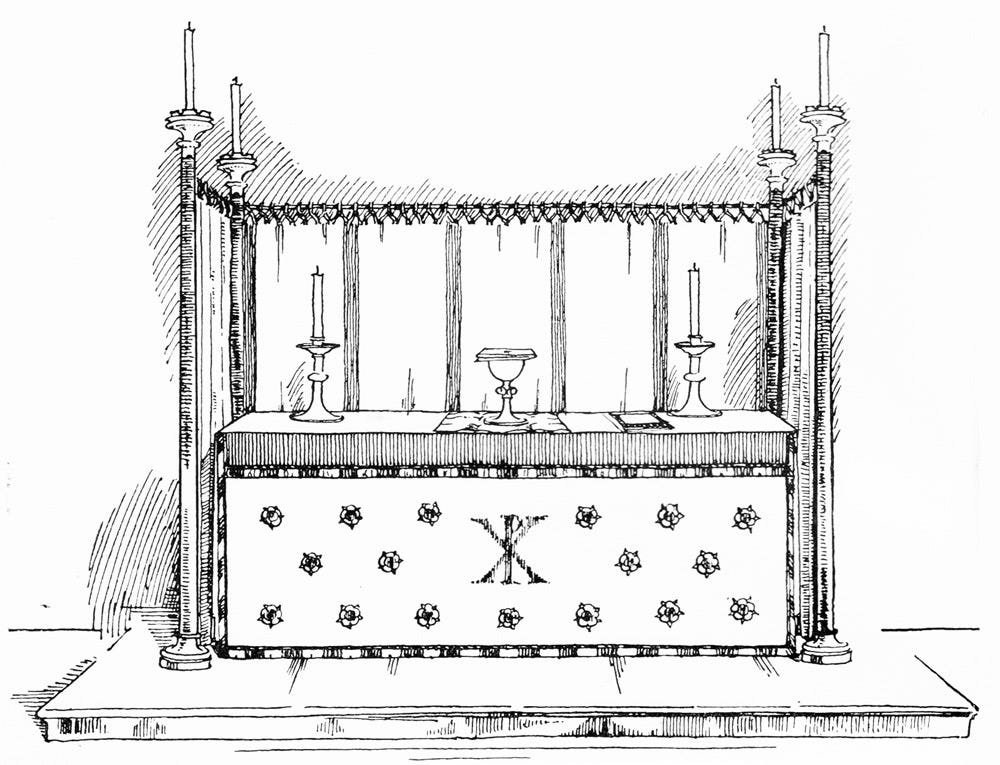

But it would be the late 19th and early 20th Century Catholic Anglicans that would counter-balance then-contemporary Roman practice with synthesizing English 1549 use1—not the Puritan-minded obligatory laicization of priestly vestments to choir-dress—alongside the post-Reformation reality of the Church in England. The Alcuin Club remains the great resource for this sensibility, alongside Percy Dearmer, and Warham Guild.

I have considered myself a Prayer Book Catholic for as long as I have been a priest, which last week marked seven years. But, as with all “churchmanships,” there is a vacillating propensity towards rigidity or laxity, especially which BCP? and how much/little one can mangle?.

Archbishop Rowan Williams says in his usual eloquence what I have been trying to put my finger on for a number of years: Prayer Book Catholicism is not Prayer Book Fundamentalism:

What exactly Cranmer or others might have meant by the words of particular prayers, or even by the ordering of particular elements of the liturgy, matters rather less, I dare to say, than the fact of an invitation to inhabit such a world. And what the tradition of Prayer Book Catholicism in Anglicanism represents is, above all, an attempt to receive flexibly and imaginatively the legacy of the Prayer Book’s words and structures; to ease and resolve some of the tensions that arise; to smooth out the edges of controversial sharpness in phrases and practices, and to illustrate how it’s possible, once again, for liturgy to be both profoundly anchored in a common and creative past and to be flexible and responsive in the present.

We know that the purpose of establishing the Prayer Book Society was not Prayer Book fundamentalism, and that’s an important point. We’re not actually talking about a sacred text that fell from heaven. We’re talking about a very remarkable historical and spiritual experiment. And like all good experiments, when it is repeated, it may adjust itself to deal with imbalance; to deal with areas where it is not as successful as it might be. It continues to provoke questions about itself and to renew its own life. It’s part of a wider process of how the Church thinks and rethinks its worshipping identity across the centuries.2

This explains the ethos I have had with liturgy, as I have tried to find my liturgical footing: then learning, the tendency is to find a specific structure and entrench. And many voices would like for you to follow the Prayer Book their way, the one and only. Some, going full Laudian, advocate a degree of conformity in the particulars3 that the Anglican Church, both then and now, did not and does not uphold.4

This is of course not to say that there should be chaos, or so much change as to make a tradition unrecognizable: this was the error or the popular interpreters of the Liturgical Movement, as well as the Convergence Movement (origin of Three Streams Anglicanism). There is an abundance of critique of the post-1960s ways of free expression of the service (viz 1979 BCP Rite III or Three Streams Worship), so will not be taken up as much here. However, it does mark the other pole of two extremes: one which creates a structure, and the other which eschewes it. To balance these, one must lean on Tradition.

A Living Tradition

Jaroslav Pelikan said of Tradition:

Tradition is the living faith of the dead; traditionalism is the dead faith of the living. Tradition lives in conversation with the past, while remembering where we are and when we are and that it is we who have to decide. Traditionalism supposes that nothing should ever be done for the first time, so all that is needed to solve any problem is to arrive at the supposedly unanimous testimony of this homogenized tradition.

Liturgical is one of the most appropriate adjectives to apply to this quote: Liturgy, too, can be the dead faith of the living, or the living faith of the dead.

When I was active at an Eastern Orthodox parish, I found that I could visit many different parishes, and all were familiar—even harmonious—such that worship was undistracted, yet, the choreography, musicality, and devotional custom (joyous, somber, rigid, casual) varied significantly. And this was Good. While I discerned I was not called to serve in the Eastern Orthodox church, I have continued to benefit from the experience.

I had read my way into Orthodoxy, but found on the ground experiences wildly different — divergent— from my reading; not in the liturgy but in theology and pastoral care. By contrast, I did not read my way into Anglicanism, I was discipled into it. Because of this my archetype was not according to a critical text, a specific reading of a prayer book, or a social media narrative, but an invitation to live within the tradition, the living faith.

This last week was the seventh year of my ordination to the priesthood, following my tenth year as a deacon. Most of my sense of Liturgy and worship is founded on Orthodox theology, translated into Anglican contexts by the bishop who mentored me, Winfield Mott, as I prepared for the diaconate, and in the subsequent years as I prepared for the priesthood. Through passing down his episcopal teaching—not with textbooks or YouTube videos, but by communicating the living faith in dialogical conversation, in harmony with Meyendorff and Schmemann— he presented a catholic orthodoxy in a Western “Anglo” context which provided me a sensibility for integrating “liturgical continuity” without “liturgical fundamentalism” (a term equally applicable to some Missal Anglo-Catholics as much as some 1662/1552 Low Churchmen5).

Back to the 1662 Book of Common Prayer (again)

This means that while I am a strong advocate for familiarity with the 1662 I do not think it should be the only text a church uses for worship, much less the best one for all contexts. And even if 1662 were the only Book, it does not mean that one must always do only what the 1662 prescribes and proscribes. The history of the 1662 itself contradicts this interpretation. For example, a ruling in 1789 deemed that the First Lord’s Prayer of the Holy Communion may be omitted, but the rubrics were never modified to reflect that. Services were authorized to be shortened in the 19th century, again without rubrics modified. Other ‘uses’ of the 1662 have since become accepted organically, without compromising the ‘norm’ the 1662 establishes as a foundation for other subsequent Prayer Books. Authorization in this way becomes an economia of the liturgy, a pastoral application of a rule without a compromise of it.

Thankfully while the 1662 bears the indelible mark of Cranmer, most especially in eloquence, it is not the liturgical product of just Cranmer. Its subsequent revisions are in the continuity of bishops and theologians, including the liturgical prowess of the Caroline Divines,6 like Bishop Cosin who helped with the 1662 revision. While not ideal to many on the established church side, what was retained was still a catholic text for public worship. As a compromise document, much like the 39 Articles, it is nuanced insofar as how the intention and celebration of the book is to be applied.

In this way, contemporary books that incorporate the use of the Book of Common Prayer since then, such as Bishop Paul Thomas, SSC, Using the Book of Common Prayer for the Prayer Book Society UK,7 are such a boon for Prayer Book Spirituality: they make a text into a living document. To be clear: rubrics should be followed8 and are there for good reason,9 just as in the Ordinal bishops are to be obeyed10, but in that there is more room for “mangling” devotion than most rigid views of the [right] Anglican way allow for.

And this rigid view is not only not the way of Anglicanism, it is not the Catholic, and it is not the Orthodox. People and cultures are diverse, at local community level as much as national or ethnic group; even if the liturgy is the same, devotional practice varies. Conformity to using a Prayer Book is not the same as uniformity to one expression of it, and in most contexts, it is not uniformity to only one book. While the 2019 is the provincial revision of the prayer book, the constitution includes many lawful books.11

In fact, 1662 itself, even in its first decades, while under an Act of Uniformity (1662), did not have uniform worship so much as an agreed Prayer Book to abide by, even before the Toleration Act of 1688: there were churchmanship parties, and emphases, which found expression around the use of one prayer book.

The Classical text is valuable because it participates in the Great Tradition; not ignoring the Reformation, but celebrating what it brought to Christendom. But the Classical text is not the end-all of liturgy: it was a point in time, and providence has deemed it to be “a standard,” through which the Missal tradition and the Liturgical Movement have brought their own Catholic and Ecumenical insights, respectively.

To see the Classical text as the cohesive core to the English church’s liturgy, which could not be distilled more minimally, allows one to re-incorporate devotions appropriate for churchmanship. For the Ritualist or Tractarian, that would be adding devotions excised in the controversy of the canonical century of the Reformation. For the evangelical, it could be including extemporaneous times of prayer and devotion within the permissible portions of the liturgy (e.g., “Prayers of the People”) or prayers for healing as a devotion following the taking of communion. For others, that might mean a re-valuation if the 1549, as in the Anglican Service Book, American Missal, and customary of Missionaries of St John, and as permitted by the 2019 BCP rubrics.12

Accepting diversity

But is there precedent for such a ‘broad’ liturgical perspective?

Most notably, there is a difference between contradicting the Prayer Book, and having devotional supplements: as long as what is advocated has precedent in Scripture or in Tradition (being prior authorized prayers, themselves scriptural), localized Eucharistic devotions do indeed have precedent in the church’s tradition, and especially in the English church’s tradition.

One can see this in how Andrewes celebrated the liturgy in his chapel, which resembles the 1928 more than 1662, deviating from the 1559.13

Or as Palmer and Hawkes note in Readiness and Decency (1946), on the use of the 1662 Prayer of Oblation before the distribution of Communion (like 1928/1979/2019 ) instead of after, which Cranmer most certainly did not intend in his 1552 revision.:

This Prayer of Oblation would be a great aid to devotion if said immediately after the Prayer of Consecration. Can it legally be used at that point? Many holy and learned men have thought so. Bishop Overall (d 1619) used it there. (Cosin, Vol. v, p. 114.) Bishop Cosin (d. 1672) advocated it. Dr Thorndike (d. 1672) advocated it. (Works, vol. v, p. 246.) Archbishop Sharp (d. 1712) preferred it there. (Life, vol. i, p. 355.) The Scottish Liturgy of 1635 placed it there again. The Non-Jurors restored it to this place. It became the Use of the Scottish and American, the South African and other Missionary Churches. Bishop Wilson (d. 1775) desired it. (Works, Vol. v, p. 73.) The Convocations of Canterbury and York have approved it in connection with Prayer Book revision.

And in the Missal tradition, The Society of the Holy Cross (S.S.C) took this liturgical philosophy up after the later Tractarians:

In 1685, a clergyman named Sparkes was prosecuted in the Court of King's Bench for using "other prayers in the Church and in other manner" than those provided in the Prayer Book. He was acquitted on the ground that he had used "other forms and prayers" not instead of those enjoined, but in addition to them. S.S.C. therefore was introducing no innovation when it turned its eyes elsewhere for guidance in those matters which the Prayer Book omitted, but nowhere prohibited. And where more fittingly could it turn its eyes than to the prevailing Western Rite? — The Catholic Movement and the Society of the Holy Cross (1931) (emphasis added)

The Society of the Holy Cross of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, through the devotion of its members, provided us with what became The English Missal, which was designed to provide Catholic (at times Tridentine-Roman, other times “Sarum”) devotions to the 1662, while still keeping the Prayer Book as the book.

Finding Continuity

In a way, Prayer Book Catholicism is a kind of Anglo-Catholicism, in that it accomplishes the Great Tradition by worshipping with the Book of Common Prayer—hopefully classical—considered as a sufficient, valid catholic text, in which additional historic devotions do no harm, nor “make more valid” the text, as some ritualists, past and present, often assert in relation to 1662 (or 1979, or 2019, for that matter).

It is out of this that Common Prayer so often repeated as “Uniform Prayer” (common: “shared equally by two or more”) is more Prayer in the Commons (common: “public” or “widespread”), as opposed to private/privy prayer. In this way true Common Prayer is not uniformity of the present, whatever committee happens to invent new liturgies (as in 1979 Prayer C), but Public Prayer, in harmony with the Community of Saints throughout the age of the Church. Common in this way is Catholic: “that which has been believed everywhere, always, and of all people: for that is truly and properly Catholic.” (Vincentian Canon). To have Common Prayer means it must recognizably participate in—inhabit, to use Williams’ word—the Catholic Faith as much as the book of one particular era. This test gives boundaries to reject some (e.g., 1979 Prayer C), but continue to support others (e.g., a high church use of 1662).

Martin Thornton, in the preface to English Spirituality

At the heart of Anglicanism is the insistence on historical continuity; if our claims are true then our spirituality, that is our total expression of Christian life, as well as our theology, liturgy, and polity, must be retraceable through the medieval and patristic ages to the Bible. I have tried, therefore, to portray the English School as a living tradition, drawing its inspiration and character from all ages, while set within the glorious diversity of Catholic Christendom. Rather than preoccupation with the past, I believe that it is this comprehensive view which can inspire creative insights into the spiritual needs of the twentieth century: a good tree, especially an ancient one, bears new fruit only when attention is paid to its roots.

Fundamentalists would have many believe that all parishes are to be exactly uniform, is to ignore that history is not so univocal or static: but being in continuity with the “glorious diversity of Catholic Christendom” as the English/Anglo expression of the catholic faith (in contrast to Roman)14 does predispose towards a continuity and integration of that which came before, most especially being connected to the classical Prayer Book tradition.

Fr J. M. Kelman

ιμκ

The basis being the Ornaments Rubric

Rowan Williams, Thomas Cranmer: A Prayer Book Catholic?, Faith and Worship #93

“After the Anglican Archbishop William Laud made a statute in 1636 instructing all clergy to wear short hair, many Puritans rebelled to show their contempt for his authority and began to grow their hair even longer” — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laudianism

I am aware that a great many specialists in divergent churchmanships are dedicated to promulgating a more rigid — authoritarian — but for them personally agreeable Anglicanism, especially insofar as deconstructing Anglo-Catholics. The Refrain, found in Reformation and Latitudinarian circles: “Shuffle off to Rome.”

The former at least has Ritual Notes to pore over; presumably 9th edition!

See Dom Benedict Andersen, The Caroline Liturgical Movement

Or, from a Reformation low-church perspective, Bray and Keane’s How to Use the Book of Common Prayer: A Guide to the Anglican Liturgy which helpfully establishes the Cranmerian logic, retained in the 1662, and helps inform better classical use of the 1979/2019.

Oath of Conformity, from the 2019 Ordinal:

I, N.N., do believe the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments to be the Word of God and to contain all things necessary to salvation, and I consequently hold myself bound to conform my life and ministry thereto, and therefore I do solemnly engage to conform to the Doctrine, Discipline, and Worship of Christ as this Church has received them.

Except, of course, for the Black Rubric

Oath of Canonical Obedience, from the 2019 Ordinal:

“And I do promise, here in the presence of Almighty God and of the Church, that I will pay true and canonical obedience in all things lawful and honest to the Bishop of —, and his successors, so help me God.”

ACNA Constitution:

“We receive The Book of Common Prayer as set forth by the Church of England in 1662, together with the Ordinal attached to the same, as a standard for Anglican doctrine and discipline, and, with the Books which preceded it [e.g., 1549, 1552, 1559, 1637], as the standard for the Anglican tradition of worship.”

ACNA Canons, Title II, Canon 2 Of the Standard Book of Common Prayer Section 1 -

“The Book of Common Prayer as set forth by the Church of England in 1662, together with the Ordinal attached to the same, are received as a standard for Anglican doctrine and discipline, and, with the Books which preceded it, as the standard for the Anglican tradition of worship. The Book of Common Prayer of the Province shall be the one adopted by the Anglican Church in North America. All authorized Books of Common Prayer of the originating jurisdictions shall be permitted for use in this Church.”

The books I am aware of which had use in the originating dioceses/churches prior to the formation of the ACNA:

1549, 1662, 1928, 1962, 1979, REC 2003, RECML 2003, Common Worship, An Anglican Prayer Book (2008), Anglican Missal, English Missal, American Missal, Anglican Service Book

“any service contained in this Book may have the contemporary idiom of speech conformed to the traditional language (thou, thee, thy, thine, etc.) of earlier Prayer Books. Likewise, the ordering of Communion rites may be conformed to a historic Prayer Book ordering” —BCP2019, p. 7

“Within the Prayer of Consecration, Andrewes restored the old manual acts, retained in 1549 but omitted in 1552. Perhaps more importantly for the development of the Anglican Liturgy, Andrewes skillfully reordered the prayers of the 1552/1559 Liturgy, so as to transform it from being a series of Communion devotions into a true Liturgy, after the patterns of Christian antiquity. The following chart shows Andrewes' order as compared to 1549 and 1552:”

These are expressions within particular traditions, not necessarily confined to a particular place or people group. Hence Roman Catholicism finds expression locally-adapted in Latin America that is distinct from European Romanism, and Alaskan Orthodoxy has a different temperament from African Orthodoxy, or African Anglicanism—in its many expressions (cf. Kikuyu controversy, and Bishop Frank Weston) is quite different from American Anglicanism. Yet these are discernible traditions, locally adapted not just by the bishops over them, but the liturgical history in which they participate.